|

"The fact that an opinion has been widely held is no evidence whatever

that it is not utterly absurd; indeed, in view of the silliness of the

majority of mankind, a widespread belief is more likely to be foolish than

sensible."

Bertrand Russell.

"The fact that an opinion is widely held among the managers of the mass

media is no evidence whatever that it is not utterly absurd. In view of

their need to accommodate themselves to the real structures of power in

the economic systems within which they are embedded, the uniformity of

their belief systems is hardly surprising."

Anonymous

paraphraser. |

June 12, 2008

Annals of Propaganda

Time For Paradigm Refreshment

For students of propaganda the New York Times is the channel to watch.

As a supernova is to astronomers, the "newspaper of record" today treated us

to its journalistic equivalent, an explicit attempt at paradigm refreshment.

I am using the term paradigm in its modern usage, meaning a framework of

reference where "framework" stands for a set of underlying assumptions which can

be relied upon in discourse without the need of further proof.

An essential paradigm for every modern imperialist state is the belief in the

unique superiority of its institutions. The two imperialist states which

Anglo-American imperialism contended with in the 20th century were imperial

Japan and the Third Reich. Their imperialist paradigms are or were, American

Exceptionalism, hakko ichiu, and the Fuehrer Principle, respectively.

Hakko ichiu, literally "eight-sided tent," is an interpretation of the

speech Japan's legendary first emperor Jimmu (711 BC - 585 BC) made upon

ascending the throne. The interpretation, made by Japanese nationalists early in

the 20th century, was that Jimmu had commanded the Japanese people to spread

their superior way of life (the eight-sided tent) until it covered the world.

As a paradigm, it became the framework of reference for an important foreign

policy statement made by the Japanese Prime Minister, Prince Fumimaro Konoe, on

August 1, 1940. Wikipedia refers to this speech as follows:

…the second Konoe administration issued a white paper titled

“Fundamental National Policy”, which opened with these words [hakko

ichiu], and in which Prime Minister Konoe proclaimed that the basic aim of

Japan's national policy was "the establishment of world peace in conformity

with the very spirit in which our nation was founded" and that the first step

was the proclamation of a "new order in East Asia"

It is in this sense, i.e., exporting a superior way of life as a cover for

imperialist expansion, that US propaganda is closer to that of Imperial Japan

than it is to that of the Third Reich. The latter's propaganda was more racial

and less hypocritical. Its propaganda said simply that racially superior Germans

had a superior right to the lands occupied by "inferior races."

President Bush, especially after the collapse of the "weapons of mass

destruction" rationalization, now relies exclusively on the US equivalent of

hakko ichiu, i.e., the US invasion of Iraq is an example of America's

magnanimous export of its superior institutions.

Unfortunately, Bush's mindless reliance on the American Exceptionalism

paradigm to support what is widely perceived as a lie threatens to destroy the

paradigm itself. The US propaganda apparatus, the keepers of this essential

paradigmatic prop of US imperialism, recognizes the impending catastrophe.

Against the background of the ostensible US [regime] change being offered by

Barack Obama's candidacy, there have been two additional propaganda events in as

many days, both of which are attempts at damage control:

- A US Supreme Court ruling

in favor of the Guantanamo prisoners

- The appended article, "Unlike Others, U.S. Defends Freedom to Offend in

Speech."

Astonishingly, the "kicker" for the article, a journalistic

term designating the category of the story, is, "American Exceptionalism."

That's the supernova, an explicitly literal attempt, by the flagship of the

US propaganda flotilla, to repair a named propaganda paradigm.

How good is the Times' effort at damage control? It would work on Rush

Limbaugh's dwindling herd of ditto-heads, except that their Leader has told them

the Times is staffed by Liberal "America haters." What about the rest of us?

In my opinion the article is superficial and therefore unconvincing. It

refers to laws against "hate speech" in many countries and Canada in particular.

It contrasts the situation in the US, whose commitment to Free Speech, it

alleges, is so extreme, i.e. "exceptional," that it does not have such laws. In

fact, this could be interpreted as proving the opposite. For a coordinated,

self-censoring, patriotic mass media, press laws are superfluous. The patriotic

media knows its job is to create a climate of public opinion favorable to the

state's policies. Indeed, the absence of such laws might be exploited as a cover

for the real state of affairs, rendering the media all the more effective as

covert agents of the state. This is, in fact, the strategy of the article.

It is my contention that the US media are self-censored and

overwhelmingly patriotic. As evidence, I would cite the fact that, to my

knowledge, no US mass medium has ever aired the extremely important issue of

Bush's war criminality. The following is a concocted example of the type of

article which the Times, as long as the US state exists in its present form,

will never publish.

|

June 12, 2008

American War Crimes

Note from the Managing Editor

As reported previously, the Management of the New York Times has

sponsored a panel of distinguished experts in the field of

international law, under the chairmanship of Harvard Law School Dean

Elena Kagan, to examine the important question of whether President

George W. Bush has committed war crimes. The panel concluded its

deliberations yesterday and the following essay reports their

finding.

The Management wishes to emphasize that the panel's conclusions

do not have the force of law. The panel was convened for the purpose

of airing an issue of critical importance. The Management believes

that it is fulfilling its obligation to the national interest, as

custodians of this journal, to do so.

Jill Abramson |

Harvard Law Panel: Bush Is A War Criminal

By MADA TRIPTYCH

Harvard Law Dean Elena Kagan addresses the

distinguished panel of jurists, Ronald Dworkin, Leon Kass, Richard

Posner, and Michael Sandel. | A distinguished

panel of international law experts, chaired by Harvard Law School Dean

Elena Kagan, and meeting over the past week to examine the question of US

war crimes, presented its findings today. The panel agreed unanimously

that President George W. Bush is a Class A war criminal as defined under

the International War Crimes Tribunal held in Nuremberg immediately after

World War II.

Their conclusion included the recommendation that the US President be

immediately turned over to Interpol and held in custody in preparation for

trial by the International Criminal Court in The Hague. The panel noted

that the Bush administration, with then Secretary of State Colin Powell

acting as the spokesman, had removed the US as a signatory to the treaty

establishing the ICC before invading Iraq. It emphasized, however, that no

state can exempt itself or its officials from the Nuremberg laws.

Speaking privately, Dean Kagan predicted that, following the precedent

set at Nuremberg in the cases of the Nazi leaders Herman Goering, Hans

Frank, Alfred Jodl, Wilhelm Keitel, and Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the outcome

of the ICC trial would be a guilty verdict and a sentence of death by

hanging.

The same verdicts and sentences were meted out in the Tokyo trials to

Akira Muto, Heitaro Kimura, Hideki Tojo, Iwane Matsui, Kenji Doihara, Koki

Hirota, and Seishiro Itagaki.

At the time of these executions, the opinion was widespread in the

defeated Axis countries that these harsh sentences were examples of

"victor's justice." The US Secretary of State at the time, James F.

Byrnes, vigorously defended the trials as an essential advancement in

international law which would prevent future wars, adding that the new

universal principles would apply to future US leaders as well.

Melinda Bozak in Washington contributed research for

this article.

Not Copyright 2008 The New York Times

Company |

Also, the article cites many examples of the judicial enforcement of

restraints on free speech that have occurred in other countries, but fails to

mention the recent non-judicial expulsion from employment of Dan Rather and

several co-workers in connection with the airing of Bush's going AWOL when he

was supposed to take his flight test while in the Texas Air National Guard. It

also conveniently ignores the US' long and successful campaign to destroy the

Communist Party of the USA, the jailing of Eugene Debs for his antiwar advocacy

during World War I, and the infamous Palmer Raids in the 1920's.

It has been said that freedom of the press matters only to the people who own

the printing presses. If the corporations who own the presses also own the

government, then the whole issue of freedom of the press becomes irrelevant.

OTTO

June 12, 2008

American Exception

Unlike Others, U.S. Defends Freedom to Offend in Speech

By ADAM LIPTAK

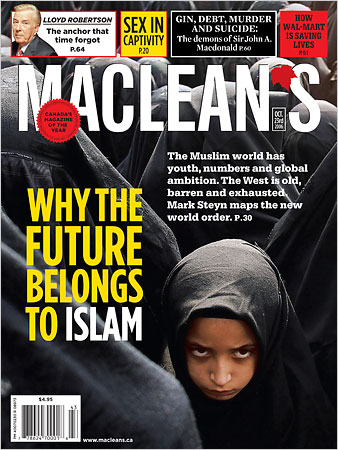

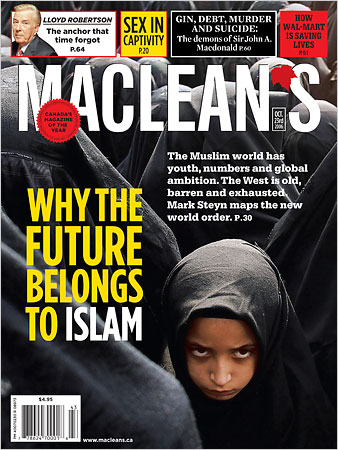

The British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal will soon

rule on whether the cover story of the October 23, 2006, issue of

Maclean’s magazine violated a provincial hate speech

law. |

VANCOUVER, British Columbia — A couple of

years ago, a Canadian magazine published an article

arguing that the rise of Islam threatened Western values. The article’s tone was

mocking and biting, but it said nothing that conservative magazines and blogs in

the United States do not say every day without fear of legal reprisal.

Things are different here. The magazine is on trial.

Two members of the Canadian Islamic Congress say the magazine, Maclean’s,

Canada’s leading newsweekly, violated a provincial hate speech law by stirring

up hatred against Muslims. They say the magazine should be forbidden from saying

similar things, forced to publish a rebuttal and made to compensate Muslims for

injuring their “dignity, feelings and self-respect.”

The British Columbia Human Rights

Tribunal, which held five days of hearings on those questions here last

week, will soon rule on whether Maclean’s violated the law. As spectators lined

up for the afternoon session last week, an argument broke out.

“It’s hate speech!” yelled one man.

“It’s free speech!” yelled another.

In the United States, that debate has been settled. Under the First

Amendment, newspapers and magazines can say what they like about minorities and

religions — even false, provocative or hateful things — without legal

consequence.

The Maclean’s article, “The Future Belongs to Islam,” was an excerpt from a

book by Mark Steyn called “America Alone” (Regnery, 2006). The title was

fitting: The United States, in its treatment of hate speech, as in so many other

areas of the law, takes a distinctive legal path.

“In much of the developed world, one uses racial epithets at one’s legal

peril, one displays Nazi regalia and the other trappings of ethnic hatred at

significant legal risk, and one urges discrimination against religious

minorities under threat of fine or imprisonment,” Frederick Schauer, a professor

at the John

F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, wrote in a recent essay

called “The Exceptional First Amendment.”

“But in the United States,” Professor Schauer continued, “all such speech

remains constitutionally protected.”

Canada, England, France, Germany, the Netherlands, South Africa, Australia

and India all have laws or have signed international conventions banning hate

speech. Israel and France forbid the sale of Nazi items like swastikas and

flags. It is a crime to deny the Holocaust in Canada, Germany and France.

Earlier this month, the actress Brigitte

Bardot, an animal rights activist, was fined $23,000 in France for provoking

racial hatred by criticizing a Muslim ceremony involving the slaughter of sheep.

By contrast, American courts would not stop a planned march by the American

Nazi Party in Skokie, Ill., in 1977, though a march would have been deeply

distressing to the many Holocaust survivors there.

Six years later, a state court judge in New York dismissed

a libel case brought by several Puerto Rican groups against a business executive

who had called food stamps “basically a Puerto Rican program.” The First

Amendment, Justice Eve M. Preminger wrote, does not allow even false statements

about racial or ethnic groups to be suppressed or punished just because they may

increase “the general level of prejudice.”

Some prominent legal scholars say the United States should reconsider its

position on hate speech.

“It is not clear to me that the Europeans are mistaken,” Jeremy Waldron, a

legal philosopher, wrote in The New York Review of Books last month, “when they

say that a liberal democracy must take affirmative responsibility for protecting

the atmosphere of mutual respect against certain forms of vicious attack.”

Professor Waldron was reviewing “Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A

Biography of the First Amendment” by Anthony

Lewis, the former New York Times columnist. Mr. Lewis has been critical of

efforts to use the law to limit hate speech.

But even Mr. Lewis, a liberal, wrote in his book that he was inclined to

relax some of the most stringent First Amendment protections “in an age when

words have inspired acts of mass murder and terrorism.” In particular, he called

for a re-examination of the Supreme Court’s insistence that there is only one

justification for making incitement a criminal offense: the likelihood of

imminent violence.

The imminence requirement sets a high hurdle. Mere advocacy of violence,

terrorism or the overthrow of the government is not enough; the words must be

meant to and be likely to produce violence or lawlessness right away. A fiery

speech urging an angry mob to immediately assault a black man in its midst

probably qualifies as incitement under the First Amendment. A magazine article —

or any publication — intended to stir up racial hatred surely does not.

Mr. Lewis wrote that there was “genuinely dangerous” speech that did not meet

the imminence requirement.

“I think we should be able to punish speech that urges terrorist violence to

an audience, some of whose members are ready to act on the urging,” Mr. Lewis

wrote. “That is imminence enough.”

Harvey A. Silverglate, a civil liberties lawyer in Cambridge, Mass.,

disagreed. “When times are tough,” he said, “there seems to be a tendency to say

there is too much freedom.”

“Free speech matters because it works,” Mr. Silverglate continued. Scrutiny

and debate are more effective ways of combating hate speech than censorship, he

said, and all the more so in the post-Sept. 11 era.

“The world didn’t suffer because too many people read ‘Mein Kampf,’ ”

Mr. Silverglate said. “Sending Hitler

on a speaking tour of the United States would have been quite a good idea.”

Mr. Silverglate seemed to be echoing the words of Justice Oliver Wendell

Holmes Jr., whose 1919 dissent in Abrams v. United States

eventually formed the basis for modern First Amendment law.

“The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in

the competition of the market,” Justice Holmes wrote.

“I think that we should be eternally vigilant,” he added, “against attempts

to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught

with death.”

The First Amendment is not, of course, absolute. The Supreme Court has said

that the government may ban fighting words or threats. Punishments may be

enhanced for violent crimes prompted by racial hatred. And private institutions,

including universities and employers, are not subject to the First Amendment,

which restricts only government activities.

But merely saying hateful things about minorities, even with the intent to

cause their members distress and to generate contempt and loathing, is protected

by the First Amendment.

In 1969, for instance, the Supreme Court unanimously overturned

the conviction of a leader of a Ku

Klux Klan group under an Ohio statute that banned the advocacy of terrorism.

The Klan leader, Clarence Brandenburg, had urged his followers at a rally to

“send the Jews back to Israel,” to “bury” blacks, though he did not call them

that, and to consider “revengeance” against politicians and judges who were

unsympathetic to whites.

Only Klan members and journalists were present. Because Mr. Brandenburg’s

words fell short of calling for immediate violence in a setting where such

violence was likely, the Supreme Court ruled that he could not be prosecuted for

incitement.

In his opening statement in the Canadian magazine case, a lawyer representing

the Muslim plaintiffs aggrieved by the Maclean’s article pleaded with a

three-member panel of the tribunal to declare that the article subjected his

clients to “hatred and ridicule” and to force the magazine to publish a

response.

“You are the only thing between racist, hateful, contemptuous Islamophobic

and irresponsible journalism, and law-abiding Canadian citizens,” the lawyer,

Faisal Joseph, told the tribunal.

In response, the lawyer for Maclean’s, Roger D. McConchie, all but called the

proceeding a sham.

“Innocent intent is not a defense,” Mr. McConchie said in a bitter criticism

of the British Columbia law on hate speech. “Nor is truth. Nor is fair comment

on true facts. Publication in the public interest and for the public benefit is

not a defense. Opinion expressed in good faith is not a defense. Responsible

journalism is not a defense.”

Jason Gratl, a lawyer for the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association

and the Canadian Association of Journalists, which have intervened in the case

in support of the magazine, was measured in his criticism of the law.

“Canadians do not have a cast-iron stomach for offensive speech,” Mr. Gratl

said in a telephone interview. “We don’t subscribe to a marketplace of ideas.

Americans as a whole are more tough-minded and more prepared for verbal

combat.”

Many foreign courts have respectfully considered the American approach — and

then rejected it.

A 1990 decision

from the Canadian Supreme Court, for instance, upheld the criminal conviction of

James Keegstra for “unlawfully promoting hatred against an identifiable group by

communicating anti-Semitic statements.” Mr. Keegstra, a teacher, had told his

students that Jews were “money loving,” “power hungry” and “treacherous.”

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Brian Dickson said there was an issue

“crucial to the disposition of this appeal: the relationship between Canadian

and American approaches to the constitutional protection of free expression,

most notably in the realm of hate propaganda.”

Chief Justice Dickson said “there is much to be learned from First Amendment

jurisprudence.” But he concluded that “the international commitment to eradicate

hate propaganda and, most importantly, the special role given equality and

multiculturalism in the Canadian Constitution necessitate a departure from the

view, reasonably prevalent in America at present, that the suppression of hate

propaganda is incompatible with the guarantee of free expression.”

The United States’ distinctive approach to free speech, legal scholars say,

has many causes. It is partly rooted in an individualistic view of the world.

Fear of allowing the government to decide what speech is acceptable plays a

role. So does history.

“It would be really hard to criticize Israel, Austria, Germany and South

Africa, given their histories,” for laws banning hate speech, Professor Schauer

said in an interview.

In Canada, however, laws banning hate speech seem to stem from a desire to

promote societal harmony. While the Ontario Human Rights Commission dismissed a

complaint against Maclean’s, it still condemned the article.

“In Canada, the right to freedom of expression is not absolute, nor should it

be,” the commission’s statement said. “By

portraying Muslims as all sharing the same negative characteristics, including

being a threat to ‘the West,’ this explicit expression of Islamophobia further

perpetuates and promotes prejudice toward Muslims and others.”

A separate federal complaint against Maclean’s is pending.

Mr. Steyn, the author of the article, said the Canadian proceedings had

illustrated some important distinctions. “The problem with so-called hate speech

laws is that they’re not about facts,” he said in a telephone interview.

“They’re about feelings.”

“What we’re learning here is really the bedrock difference between the United

States and the countries that are in a broad sense its legal cousins,” Mr. Steyn

added. “Western governments are becoming increasingly comfortable with the

regulation of opinion. The First Amendment really does distinguish the U.S., not

just from Canada but from the rest of the Western world.”

Copyright 2008 The New York Times Company