| US invasion of Iraq: First, one was certain to win; then one expected the enemy to lose; then, one was satisfied that he too is suffering; in the end, one continues the war to prevent the very thing one is perpetrating and the media have forgotten why they promoted it in the first place. |

Annals of Propaganda

The chance for the NY Times to review the book, Life and Death in the Red Army, comes along in the nick of time. With mastermind Cheney's war-fighting ability in doubt after his friendly fire took out a hunting companion, the US Army death toll lurching inevitably toward 2500, our British cohorts in Western Values sadistically beating Iraqi children, more photographic evidence of US pornographic violence perpetrated against Iraqis surfacing, and Noam Chomsky convincingly asserting that the US is the world's worst terrorist state which slyly exempted itself from the very crimes it hung Nazi war criminals for, something had to be done on the propaganda front.

How do you counter all that bad news? You can't deny that Cheney shot his hunting companion: He's in intensive care with a gunshot induced heart attack. You can't deny the other stuff either because it's on tape and film and if you deny Chomsky's assertion, knowing him, he'll produce the documentation, which will just aggravate the situation. Besides, the propaganda apparat decided long ago that he doesn't exist.

The perfect solution is to dump on an army that no longer exists. And if it happens to be the Red Army, it even helps mitigate the problem of the glut of unemployed anti-communists.

The appended NY Times book review leverages the review into a condemnation of the Red Army which, had it been written between 1941 and 1945, would have put the Times squarely on the side of, of all things, the Third Reich. Given the congruence of the Reich's and the Times' hatred of the Soviet Union this isn't in the least surprising.

Wars are massive social enterprises involving every human attribute from the noblest to the lowest form of degradation. This makes it easy for the propagandist. If he is ordered to mobilize public opinion in favor of an ally he will advertise the noble and vice versa.

It is futile to try and refute the propaganda-by-innuendo embedded in this book review, which is, essentially, that the Red Army consisted of incompetent and cowardly soldiers, driven only by their fear of their political commissars, that they were vodka-crazed rapists intent on perpetrating war crimes against German civilians. Instead I will merely present a few data points which the reader might ponder.

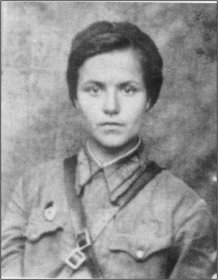

Natalia Katschuyevskaya

|

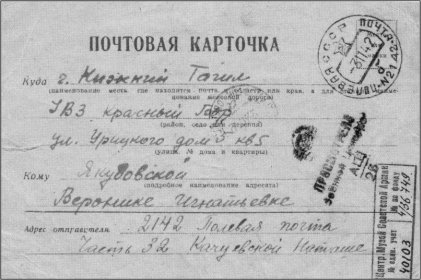

Address side of card Natalia wrote on October 29,

1942.

|

|

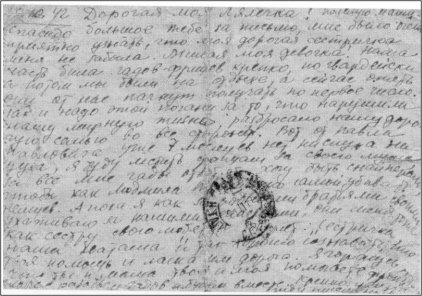

Message side of her card.

|  |

Her message:

My dear Lyaletschka,

…I'm going to get revenge against these Fritz's for my husband. These SOB's will suffer for all that. I'd like to become a sharpshooter so that I can kill these Germans myself as Lyudmilla Pavlitschenko does. For now, I take care of the wounded as if they were my own brothers. And they like me as if I were their sister, they say, "Our little sister Natasha," and it's good to know that they value your help and your tenderness.

Lyudmilla Pavlitschenko |

The picture on the right is a photo of the sharpshooter that Natalia said she wanted to emulate. At the time the picture was taken Lyudmilla was an instructor at the sharpshooter training school in the Visnyak-Moscow region. She was designated a "Hero of the Soviet Union" in 1943. She was said to have shot 309 German soldiers.

Russian women soldiers were especially notorious among German soldiers, who called them "Flintenweiber." There is no English equivalent to this term, but it translates roughly as "gun-toting broads," where I have used the vulgarity to capture the negative connotation of the original.

Natalia Kovschova and Mariya Polivanova, before setting out on a combat mission in July, 1942. |

Dear, dearest Mother,In August 1942, Natalia and her partner Mariya were ambushed. Rather than be captured the two set off handgrenades, killing themselves and several German soldiers.

…We went out at 11 o'clock at night, it was already dark. We had to go through a big forest and a rye field, there were just two of us…. We pulled out, a deep, dark night, we didn't recognize the paths. We stopped in the middle of a field. The rye around us stood man high, we couldn't see a thing. I say, "to the right," but Mascha says, "to the left." We argued and argued. Then we decided to go back a ways. We're walking — the path looks familiar, we went back and that turned out to be the right decision. Otherwise we would have landed amongst the Fritzes. That would have been something. But we were lucky. We were on the hunt for two days. In those two days, Mascha and I killed eleven Fritzes. On the 13th, we got back home late at night. Mascha now has a 103 degree fever.

These stories are taken from the book, Mascha+Nina+Katyuscha: Women in the Red Army, 1941-1945, published by the German-Russian Museum, Karlshorst, Berlin, to document an exhibition of the same name which ran from November 15, 2002 to February 23, 2003.

The book contains a classic photo of a combat nurse tending a wounded soldier in a trench:

An unknown Red Army nurse in an unknown battle,

1943. |

The book documents dozens of such stories and, with certainty, there are millions more that will never be documented. It is also a certainty that an anti-communist hack writing for the NY Times will never report a single one.

OTTO

Books of The Times | 'Ivan's War'

| |

|

What was life like in the armed services for a typical Soviet soldier? Catherine Merridale, a British historian, set out to find the answer, tape recorder in hand, interviewing veterans and their relatives, and digging deep in previously unavailable sources like diaries and field reports. Her goal was to get beyond the Soviet myth of inevitable victory achieved in the name of the Communist Party, motherland and Stalin, a myth that has obscured the harsher realities of the war, the multiple failures of government officials and the often needless sacrifices of millions who fought, as the book's title has it, "Ivan's War."

No matter how bad American soldiers had it in World War II, Russians had it worse, from start to finish. Stalin's refusal to plan for a defensive war placed his troops in a disastrous position from the outset. The Soviet forces that met the Germans in June 1941 were poorly trained, poorly fed and poorly equipped. Basic training relied on wooden guns and cardboard tanks. Stalin did not like the idea of putting live weapons in the hands of ordinary citizens. "Until the end of 1939, the smart new guns were reserved for military police, and all the army's stock was locked away," Ms. Merridale writes.

The official picture of a people solidly united behind the government and the party falls apart under scrutiny. Nearly three-quarters of the infantry started life as peasants, and many had suffered the traumas of forced collectivization. Their feelings toward the regime ranged from sullen acquiescence to outright hostility, especially in Ukraine. In the early months of the war, as the Germans advanced at will, mass desertions were commonplace. Troops, seized by "tank fright," often panicked and fled.

The American experience of tight-knit platoons bound by loyalty and friendship did not exist in the Soviet armed forces. The extremely high casualty rates ensured a constant turnover in personnel. Most soldiers either died or were wounded within three months of reaching the front lines. Further, the government assigned political officers to every fighting unit to reinforce party discipline and to report on conversations. Mutual trust was impossible.

"Ivan's War" combines, quite effectively, painstaking historical reconstruction and sympathetic projection. Ms. Merridale, proceeding from campaign to campaign, describes from the top down and from the bottom up. She provides a coherent picture of the tactical decisions and industrial adjustments that altered the course of the war, and at the same time focuses on how such changes were reflected in the day-to-day experiences and feelings of the troops on the ground.

Something like despair defined the period up to Stalingrad, as the Soviet Union gave up great swaths of territory and 45 percent of its population to the Germans. Unlike the Americans or the British, Russians fought on knowing that their wives and their parents and their children were in the hands of the enemy. They were hungry, subsisting on a diet of soup, kasha, bread and tea. Rampant pilfering of army warehouses and supply trucks diverted more desirable food, as well as other war material, to the black market. Soldiers, lacking spades, dug trenches with their helmets, the same helmets in which they boiled potatoes.

Somehow, they fought on. As the Russians came to understand what was happening in captured Soviet territory, despair changed to a ferocious appetite for vengeance and, at Stalingrad, a growing confidence that the Germans could not only be stopped, but beaten. "Imagine it — the Fritzes are running away from us!" a Russian soldier wrote to his wife after Stalingrad.

The Germans, for their part, faced the disturbing possibility that the mongrel Slavic race might actually be able to fight. "The Russians are not men, but some kind of cast-iron creatures," a German soldier wrote at Stalingrad. (An intimate, and chilling, view of the German side can be glimpsed in "A Stranger to Myself: The Inhumanity of War, Russia, 1941-1944,", the diaries of Willy Peter Reese, a German soldier who died on the Eastern front, recently published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

Ms. Merridale's narrative darkens with the Russian advance into Germany. She describes an army fueled by rage and vodka, whipped into a frenzy by its political officers. The Russian soldier's "rage in battle must be terrible," a slogan at the time said, continuing, "He does not merely seek to fight; he must be the embodiment of the court of his people's justice." In practice, this meant rape, pillage and plunder on a scale that has yet to be recognized. The Red Army, Ms. Merridale writes, embarked "on an orgy of war crimes."

None of this comes out in her interviews with veterans. Their war is the official Soviet war. Ms. Merridale is understanding about why that might be. The trauma of the war was simply too much to face unflinchingly for those who lived through it. She is unsparing in her account of the terror unleashed on German civilians, but scathing about the world to which the veterans returned. For Soviet heroes, who thought they had earned the right to a less repressive society, there would be no G.I. Bill, no postwar prosperity, no sunny homecoming. Stalin had other plans. "The motherland was never conquered," Ms. Merridale mournfully concludes, "but it had enslaved itself."

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company